Finding Their Words: How Retrieval Practice Came Alive in an MLL Classroom

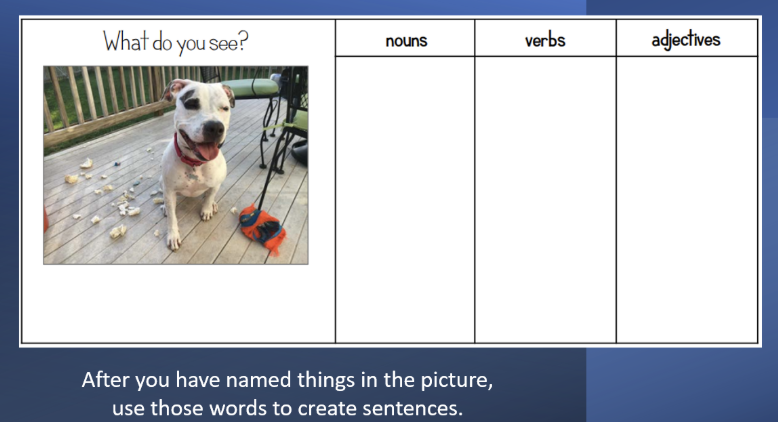

The room was unusually quiet as my students leaned forward in their chairs, eyes fixed on the picture projected at the front of the classroom. A black and white dog sat in the middle of a messy scene, stuffing spilled from a chewed-up ball, chairs were on the outside porch, with grass in the background. For some students, this image sparked instant ideas. For others, especially those who were brand new to the Multilingual Learner (MLL) program, it was simply something to point at, something familiar in an unfamiliar language.

The class was a beautiful mix of languages and stories. The students were 1st-5th grade classes. Families had come from Vietnam, the Philippines, Cambodia, Ukraine, Mexico, Korea, Venezuela, and Kenya. Some students knew only a few words in English. Others had been learning for a year or two and were just beginning to feel confident sharing their thoughts aloud. What they all had in common was the same nervous energy: testing season was approaching, and words mattered.

That day, instead of handing out worksheets or reviewing notes, I leaned into retrieval practice. Retrieval practice is the act of recalling information without having that information in front of you. As an intentional design and learning strategy, it boosts long-term retention, helps students recall information, facts, concepts, or events from their memory.

Starting With the Body Before the Brain

Before we ever touched a pencil, we stood up.

I knew my students needed a shared foundation, so we began by retrieving meaning through movement. We practiced nouns by turning our bodies into ideas: hands on hips for a person, animal ears for animals, a roof shape for places, and a ball cupped in our hands for things. Verbs came next by running in place, hopping, throwing an imaginary ball. For adjectives, we moved through the senses together.

“What do we see?” I asked, pointing to my eyes.

“A black and white dog,” someone called out.

“What might we hear?” Hands went to ears.

“He is chewing,” another student said softly.

We smelled the grass, imagined the dog tasting the stuffing, and felt the fur under our hands. Without realizing it, students were already doing retrieval work, they were pulling language from memory, attaching it to meaning, and strengthening those neural connections.

The Power of the Brain Dump

Once seated, students created a simple graphic organizer in their notebooks: noun, verb, adjective. I explained that we were going to do a “brain dump”, by writing down everything we could remember without looking at anything else.

Hands shot up.

“Dog.”

“Ball.”

“Chair.”

After giving students time to write independently, I added their answers to the board so they could check spelling and reinforce accuracy. Then something powerful happened. One student leaned over and whispered to a friend, “What do we call the thing on the dog’s neck?”

Another student jumped in.

“It’s like a rope… oh! A collar! And it has a tag.”

In that moment, retrieval practice turned into teaching others, one of the most effective ways to strengthen learning. I didn’t step in. I didn’t correct or redirect. I watched as students became resources for each other.

From Words to Sentences to Stories

We repeated the brain dump for verbs and adjectives, and then we built the first sentence on the board. We talked about capitalization and punctuation. Students copied it down, some carefully, some proudly.

For students with more English, I pushed a little further. To write another sentence. For students with less English, I suggested they practice a sentence or draw something further.

“What do you think happened before this picture?”

“What might happen next?”

“The owner got mad at the mess the dog made,” one student wrote, smiling at their own creativity. Others translated quietly for classmates who were still learning how to navigate English at all.

Post-it Notes, Flashcards, and Long-Term Potentiation

At the end of class, each student received a Post-it note. They wrote or drew a noun, verb, or adjective from memory without referencing notes from the picture of the dog. This activated concept mapping and drawing, another form of retrieval practice.

They swapped Post-its with a partner and used them like flashcards.

“What did you draw?”

“Why did you choose that?”

“Is it a noun, verb, or adjective?”

Before dismissal, I told them what they had really been doing: long-term potentiation (LTP) is strengthening their brains through repeated retrieval. I asked them to think about their Post-it overnight.

What They Remembered Still Amazes Me

The next day, I met with students one by one. Without seeing their Post-its, they explained what they had drawn or written. Two students who spoke little to no English pointed, mimed, and smiled as they showed me they remembered. Every student retrieved something that they had written or drawn in words, actions, and meaning.

By the end, they were teaching new partners again, explaining why their word mattered and how it fit into the sentence.

Retrieval practice didn’t just help them remember. It helped them belong. It gave every student, no matter their language level, a way to participate, contribute, and succeed.

And that messy picture of a dog? It turned out to be the doorway into their words.